An Environment of Corruption:

Irregularities in the licensing process of the Agua Zarca dam

A

na Hasemann Lara leans back in her chair, her dark hair pulled back in a ponytail and her arms crossed against her chest as if daring anyone to challenge her. Then she tells Revistazo all about her experiences with DESA, and the company’s efforts to portray the Lenca people as not indigenous.

Hasemann is an anthropologist with a Ph.D. from the University of Kentucky. She’s spent a good portion of her career working with the Honduran Institute of Anthropology (IHAH). Working in the contentious scene of Honduran anthropology, Hasemann has had to play many other roles that most might not associate with a scientist, including detective, advocate and rebel.

In 2010, Hasemann got a call from Sergio Rodríguez, one of the men who would later be arrested for the assassination of activist Berta Cáceres. At the time, Rodríguez was working for a company called Ecoservise. According to Hasemann, the company had been indirectly hired by Energy Developments, Inc. (DESA by its Spanish acronym) to conduct an environmental report on the land where it planned to build the Agua Zarca hydroelectric dam.

Hasemann had recently returned to Honduras from graduate school and was working as a consultant with her mother, an archaeologist.

DESA was in the middle of a strenuous process to obtain the environmental license for the dam. To do so, the company had to document the potential damages and benefits the dam might have on the surrounding environment and its residents, particularly because the project was to be built in a region populated primarily by indigenous Lenca people.

As a part of the environmental report, Ecoservise asked Hasemann to give an expert opinion on whether or not the surrounding communities were truly indigenous. Her decision would be one of the first of many controversies related to the Agua Zarca dam that would lead to accusations of corruption against 10 public officials.

“Because they are ‘Indian"

At the heart of the controversy surrounding the Agua Zarca dam is Convention 169 of the International Labor ORganization, which guarantees that indigenous communities must be consulted before a company or government begins a project that would utilize the natural resources of the lands that the people traditionally occupy.

Four Major Steps to Becoming a Dam

| Use of National Water and Operations Contract | Contract with the Ministry of Natural Resources and the Environment (SERNA) that gives permission to the dam to use the State’s water |

| Power Supply and Electricity Contract | Contract with the National Electrical Energy Company (ENEE) in which Agua Zarca agreed that it would sell the energy developed by the dam back to the State |

| Environmental License | License to operate a hydroelectric dam, given by SERNA with approval from specific departments within SERNA such as the Department of Evaluation and Environmental Control (DECA) and the Forest Conservation Institute (ICF). |

| Construction Permit | Construction permit from the Mayor’s Office of the nearest municipality to build the project in its jurisdiction. |

The convention stipulates that it applies to those who are descended from people who inhabited the nation prior to colonialization, who are culturally, socially and economically set apart from the rest of the nation, and who continue to be ruled by their own customs. It states that “self-identification as indigenous” is central to meeting the criteria of the convention and thereby earning the protection that it offers.

Hasemann travelled to the rural communities surrounding the Agua Zarca project to interview and observe the people who would be affected by the dam.

Every person she talked to self-identified as Lenca. It was clear, says Hasemann, that their indigenous identity was important to them.

She also found that none of the people she interviewed knew about DESA’s plans to build the hydroelectric dam in their communities.

Hasemann wrote up her report and stated that the people in communities surrounding the project were clearly indigenous, and under ILO Convention, their land was protected. They must be consulted before the project began.

Rodríguez read her results and was furious. He pressured Hasemann to change her findings.

Why do you say they are Indian?” he asked her.

Hasemann responded, “Because they are Indian.”

I need to know who [you spoke to] because this is a problem,” snapped Rodríguez.

Refusing to change her findings or give up her sources, Hasemann quit the project without receiving pay. She says that afterward Ecoservise hired another team of anthropologists who conducted their own study and found that the community was not indigenous. They also recommended that DESA move the project’s facilities and piping to the other side of the river where the land belonged to poorer communities in a different municipality.

Contested Land

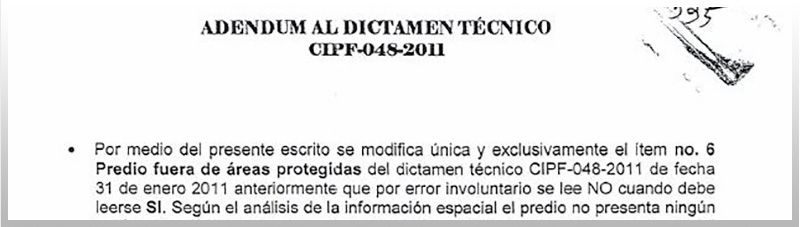

Hasemann’s report was not the first time in the licensing process that the protected status of the land had been called into question. In March of 2011, the Institute of Forest Conservation (ICF), a department of SERNA, added a single addendum to its approval of the Agua Zarca project.

Download ICF addendum

The addendum addressed the sixth point of the report which stated that the site of the project was located on protected land. It claimed that there was an error was made when filling out the report and “no” should have been marked instead of “yes”. The addendum went on to confirm the land presented no conflict.

Other SERNA departments upheld the view that the region was not protected throughout the approval process.

Déjà vu

A few years later after Hasemann’s first run-in with Agua Zarca, the Prosecutor’s Office for Ethnic Groups received a complaint from activist organizations claiming that employees of the dam were mistreating the indigenous communities and that their presence was a violation of ILO Convention 169. The Prosecutor’s Office asked the Honduran Institute of Anthropology (IHAH) to send an anthropologist to the communities to investigate the claims. IHAH sent Hasemann.

Once again, Hasemann drove the winding roads from Tegucigalpa to the remote communities on the Gualcarque River. She interviewed 14 community members as well as representatives from organizations and public officials in the area. This time the people knew about a hydroelectric dam on the river, but there was a lot of concern and confusion around the project.

Many of the community members expressed fear that if they spoke out against the dam, the local and national governments might take away welfare programs, like a subsidized food program that families relied on.

They saw the project as politicized and believed that local politicians had struck deals with DESA in return for personal benefits, like electricity for the houses of family and friends. Some people claimed that the mayor of Intibucá had “sold” three of the communities to the company in exchange for such perks.

The community also expressed frustration with the limited power they had to negotiate. They said that government failed to step in to negotiate on their behalf and protect their rights. Instead, government representatives, like the mayor of Intibucá, urged the communities to accept the benefits that the company was offering, as small as they were in reality.

Community members distrusted the company’s promises of employment, scholarships, and better roads. Moreover, they were primarily concerned about the cultivability of their lands. If the dam rented their lands for its piping and tunnels, they could lose their ability to plant crops, which for majority of the community was their livelihood.

Hasemann found that the people were confused about the project’s process of sharing information with the public. This was partly because there were multiple hydroelectric and mining companies in the area, and each one had a different project name, company name and construction company. When representatives from the companies came, they were not always clear about exactly which company and project they were there to discuss.

Hasemann left the communities with a growing concern for the strife the projects were stirring up. Communities were split between those who supported the hydroelectric projects and those who objected to them. There were even divides among the different activist organizations that opposed the hydroelectric projects. Objectors also reported experiencing abuse and persecution at the hands of projects’ employees.

Hasemann wrote up her findings and turned in her report to her boss at IHAH, but her boss refused to pass it on to the Prosecutor’s Office for Ethnic Groups. Hasemann was again hounded because of her conclusions on the Agua Zarca dam. The Prosecutor’s Office eventually got their hands on a copy of the report and it was included in the Agua Zarca files in later investigations.

An Environment of Corruption

Despite the controversy surrounding whether the Lenca had legitimate claim to the land, and whether they had been adequately consulted about the project, the Agua Zarca dam project sailed through all phases of the environmental licensing process.

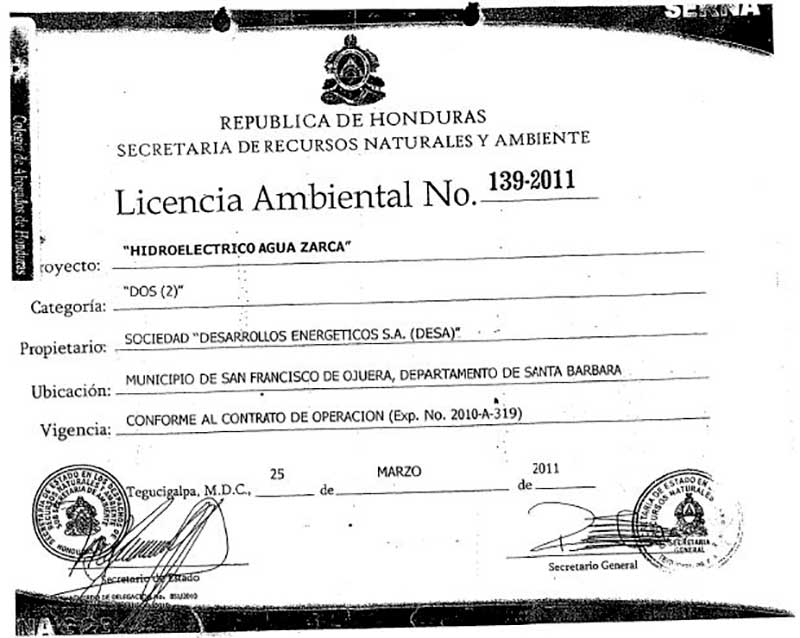

The vice-president of SERNA, Marcos Jonathan Laínez Ordoñez, approved the license on March 24, 2011. In the document, Laínez detailed three conditions to which DESA would have to comply before receiving the official license: 1) Pay a fee of 87,817.63 lempiras (around $3,725) dollars to the National Treasury, 2) Present “a Record of Dissemination of the project, with participation from the communities located in the direct area of influence…”, and 3) Comply with a standard list of mitigation measures.

Download license

Laínez signed the environmental license on March 25, 2011, one day after the license was approved. This suggests that either the Record of Dissemination (a report on how the community was informed of and consulted about the project) was never turned in, and the license was extended anyways, or that DESA completed the record and turned it in in one day.

It would have been difficult to complete the record in just one day, both because of the short time frame and also because the communities were not all willing to approve of the project. Haseman’s first report shows that people surveyed in the communities were not even aware of the project. Meetings between the community and the company were not recorded until the beginning of 2011, according to minutes kept by Cáceres’s organization COPINH. Even then the community was divided on the project. Those meetings continued well after the license was approved, without reaching a consensus.

According to the ILO convention 169, it is the government’s responsibility to see that indigenous communities are informed of the potential benefits and damages of any project that would use the natural resources on the land they traditionally occupied. Though the final approval of the communities is not required, the agreement is one of good faith that ideally trusts the government to mediate conflict between communities and companies and reach a compromise that works for both.

Laínez signed the environmental license for Agua Zarca despite the lack of a prior consultation. In May of 2012, Laínez was charged with abuse of authority for breaching ILO Convention 169.

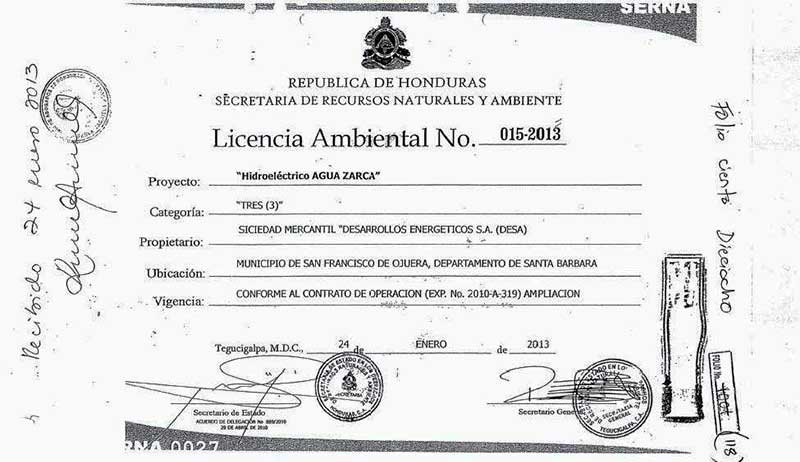

In 2012, DESA decided to increase the power supply of the Agua Zarca dam. Because it would be creating more energy than specified in the original license, the company had to seek a second environmental license. Even after Laínez had been charged with abuse of authority for the same project, the new vice-minister of SERNA, Roberto Cardona Valle, approved and signed the environmental license for the addendum on January 24, 2013.

Download license

A prior consultation had still not been conducted, and Cardona too was charged with abuse of authority in October of 2016.

In December of 2011, nine months after Laínez signed the environmental license, another act of corruption took place. The mayor of Intibucá, Martiniano Domínguez Meza, signed the construction permit for Agua Zarca. With the permit, DESA could build the project on the site it had chosen, which fell under the jurisdiction of the Municipality of Intibucá.

According to records of meetings kept by COPINH, Dominguez had been a strong advocate for the Agua Zarca project. He spoke at meetings with the community as a representative of the project to promote the benefits that DESA promised the community, like improvements in schools and free school supplies.

The meetings were an endorsement of the project, not a dissemination of its benefits and potential damages or an attempt to reach a fair agreement. They did not, therefore, fall under ILO Convention 169.

On April 14, 2013, Dominguez was charged with abuse of authority for putting his signature on the permit at the expense of the indigenous community’s rights.

Later, DESA made the decision to move the Agua Zarca site across the river. Though the dam would continue to use the same stretch of water, its piping, tunnels and spillways would run through the land on the other side, placing it within the jurisdiction of the Municipality of San Francisco de Ojuera.

The Municipal Corporation of San Francisco de Ojuera, like its neighbor across the river, approved the construction permit for the dam on its land. In December of 2017, the Mayor of the Municipality and three other members of the Municipal Corporation were also charged with abuse of authority.

Despite the corruption allegations and clear violation of indigenous rights in the licensing process of Agua Zarca, the government never revoked the dam’s licenses or contracts. DESA continued construction until July of 2017, when it suspended construction due to the tension surrounding the project. Unless the State intervenes, DESA could legally begin construction again at any time.