The Unchanging Rebel

Berta Cáceres inherited her rebellion and strength from a chain of strong women, starting with her grandmother, remembers the older sister of the late activist.

W

e were together for the last time in November when mom had an operation,” says Agustina Flores López, Berta Cáceres’s older sister. “I waited for her at my mother’s house. She called me said, ‘I have an urgent meeting. I’ll see you later.’”

It was their last night together in La Esperanza, the city where Agustina and her sibling grew up and where her mother and Berta continued to live. Berta was travelling the next morning.

Agustina waited for Berta until nine o’clock at night before she decided to go to sleep. She lay in bed angry with her sister for not taking advantage of their last few hours together.

“I was playing on my phone in bed when she finally called me,” Agustina remembers. “[Berta] said, ‘hey, you’re already asleep?’ I said, ‘How am I can I be asleep if you keep waking me up.’ She said, ‘I’m here. I’m cooking dinner.’”

Agustina left her room in her mother’s house and found Berta and friend cooking eggs in the kitchen. She teased Berta’s friend about his hat saying he looked like a Teletubby.

Early the next morning, Berta got ready to leave. Agustina tried to convince her to stay in La Esperanza or even to go with Agustina to Olancho to escape the increasing danger facing Berta. Berta confessed that she was starting to get worried.

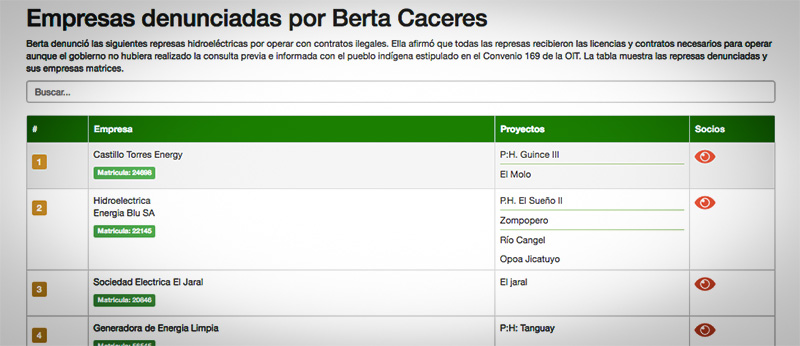

From the moment Berta reported that the government illegally extended contracts to 49 hydroelectric dams, she began to face mounting threats and persecution.

In 2013, Berta was arrested by military police for illegal possession of a firearm. COPINH maintains that the soldiers who pulled her over planted the weapon in her car. In 2013, Energy Developments, S.A. (DESA), one of the companies that Berta reported and protested, filed a complaint against Berta for supposed damages against the company, usurpation and coercion. She was acquitted in February of 2014. The municipality of Intibucá also filed a complaint against Berta and microbusinesses owners for damages and disobedience in 2015. The business owners had been protesting against the mayor’s plan to move their market out of the city center. The government also reported Berta for sedition. Neither of the two cases ever led to a formal accusation.

The government also set a military unit in front of the Agua Zarca dam facilities to protect the project in the interests of the electricity that the dam would sell to the government. The soldiers used force to remove the peaceful protestors on various occasions. They also destroyed their food and water supplies in an attempt to pressure them to leave the facilities. The worst was when a peaceful protest became a murder scene. Tomas Garcia, a community leader and protestor, began to speak in front of a crowd of protestors when a soldier fired at him, killing him and injuring his teenaged son.

According to Berta’s family, threats against her life also increased in the last few years. Agustina said that Berta started to receive anonymous threats over Whatsapp. According to a report by COPINH and testimonies from community members, a hitman was sent to Int bucá to threaten her. People from the community spread the word that the known hitman was in the area on orders of DESA. The hitman, Olvin Mejía, threatened Berta directly. She reported him and he was later arrested in tried. However, his case was later dropped. i

La tabla muestra las represas denunciadas y sus empresas matrices. //

clic aquí para ver

With threats rising, Berta started to feel the danger she was in.

“’I can’t stand the threats anymore,’ Berta told me. ‘They’re going to kill me,’” remembers Agustina with flicker a pain.

The Rebellios Little Sister

Augustina was 12 when Berta was born.

“I was in the sixth grade and we had to crochet a baby outfit that year,” she says. “I made a dress for Bertita.”

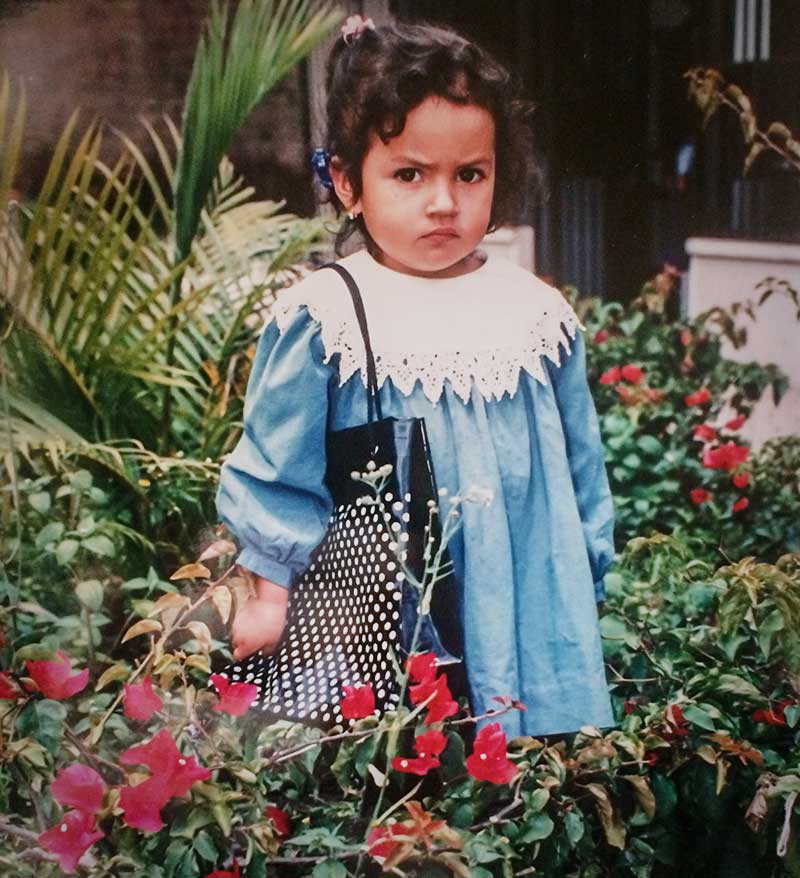

Berta was Agustina’s doll. She cared for her, bathed her, dressed her and even disciplined her in the many moments when Berta acted out.

“[Berta] was caring and spoiled. She was always a rebel,” Agustina affectionately recalls.

An Heritage

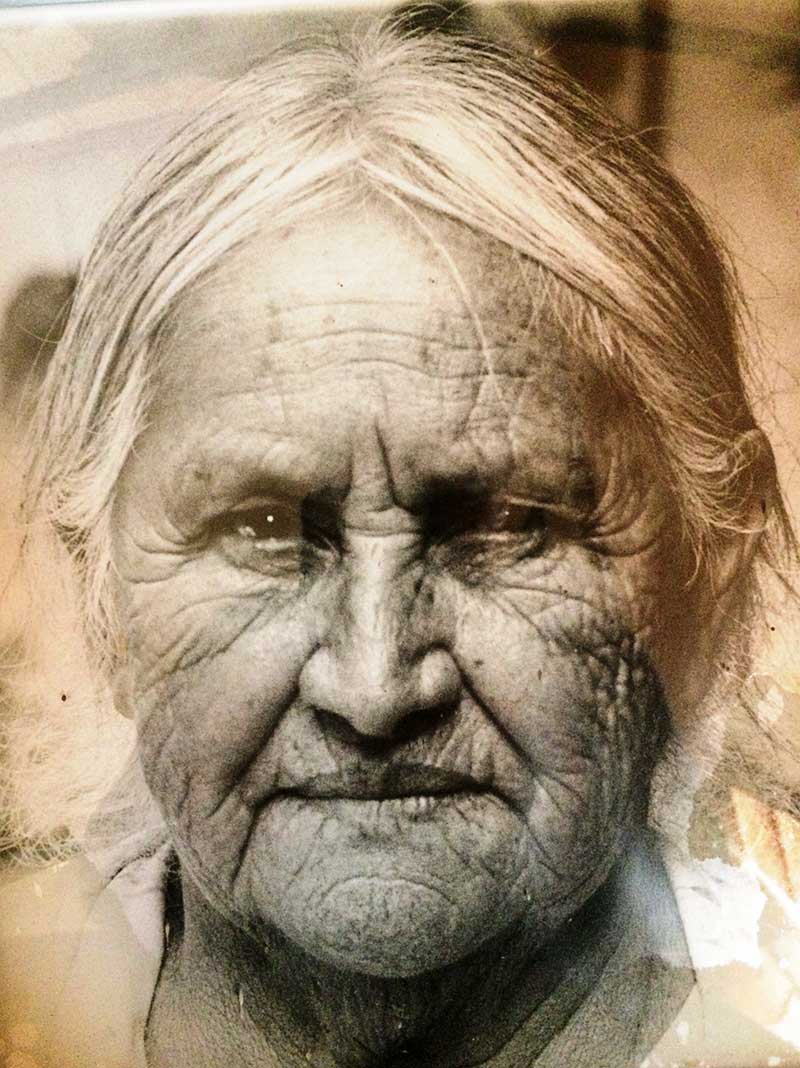

According to Agustina, Berta’s strong and rebellions character was hereditary. The chain of strong women began with her grandmother, a key figure from her childhood.

“My grandmother was a woman with so much wisdom for communicating ideas, “explains Agustina. “She had this leadership to mobilize the people.”

Agustina says that it was their grandmother that insured that all of the twelve brothers and sisters lived their childhoods like children should. They ran around with their neighbors, sat on the street corner talking, and played soccer in the street. Their grandmother established an environment of fun, solidarity, and commitment for the family.

The other key figure in the lives of the children was and is their mother, Austra Berta Flores.

Austra Berta made history in Honduras when she became the first female mayor in the country. Later, she was elected as a representative in the National Congress.

Austra Berta was a politician, a nurse and a mother of 12 children. She worked as a midwife in the rural area around Intibucá and assisted in the births of more than 5,000 babies, the majority of which were indigenous.

“We grew up with values,” says Agustina. “My mom showed us that it doesn’t matter who the person is, we have to help everyone. We grew up with no riches, no luxuries and no lack.”

Agustina and her siblings remember when crates of vegetables, milk, chicken and many other gifts would arrive at their doors late into the night from families that Austra Berta had helped at no charge.

Austra Berta would leave at all hours of the night to attend to the deliveries of women in the indigenous communities. When Berta was old enough, her mother started to take her along. According to Austra Berta, her daughter was not interested in helping at first, but she quickly got used to it. Berta would hold the candle for her mother during the births and help her prepare the babies’ clothes.

“She learned a lot from me, like to be a fighter and to speak out for the people,” says Austra Berta.

Austra Berta cared for her large family alone for most of her life. Her first husband was murdered in a time of political conflict and her second husband, Berta’s father, left his family when Berta was little.

Agustina says that through the difficulties, the 12 children learned to be united and to protect each other.

The Brilliant Fighter

Austra Berta made sure that all of her children received an education, and in the end, all became professionals.

Berta, her youngest child, studied to become a teacher, but Austra Berta says that Berta’s road to finishing her studies was a slow one.

“[Berta] was always more committed to her organizations,” explains Austra Berta.

She says that Berta was brilliant student and a fighter. Agustina remembers that from the time Berta was little she was a leader. She always had a group of little schoolgirls following her. She participated in civic engagement from elementary school. In high school, she became president of the student council.

When she was still a teenager, Berta worked with an NGO through which, according to her mother, she learned more about the rough conditions facing the indigenous community in Honduras. At that time, she also met her future husband, Salvador Zúniga.

The two married when Berta was 19 and soon after she gave birth to their first daughter, Olivia. With a baby at home, the pair decided to go to El Salvador to help support the FMLN in the its last battles in the civil war. Berta was a fighter under the alias “Laura”, the name she would later give to her youngest daughter.

Austra Berta waited the return of her daughter with great fear during the last months of the war. At that time, people often disappeared it was known that they were kidnapped, tortured and killed at the hands of the government. As a active politicians and activists, Berta’s family was not a stranger to persecution and loss.

The Arrival of the Strength

Berta and Salvador survived the war and returned to Honduras to continue their work in another fight, the fight for rights for the indigenous communities.

“[Sine] she helped in the births, she made a commitment to love them and look out for them,” says Agustina.

The couple joined forces with various other organizations to form the Civic Counsel of Popular and Indigenous Organizations in Honduras (COPINH).

“They organized COPINH to organize the indigenous, especially the Lenca,” says Austra Berta. “They trained them in their rights, in health, and in education, and how to keep from being thrown out of their territories.”

In the its first few years, COPINH organized indigenous communities to combat disforestation. It also carried out impressive marches from La Esperanza to Tegucigalpa (around 120 miles) to send a message to the nation that the indigenous population was still there and they were not going to remain silent.

“The people got excited when COPINH came,” remembers Agustina. “When COPINH arrived, the strength and the energy arrived.”

While Austra Berta was a congress representative, COPINH advocated for the ratification of Convention 169, an international convention that recognized and protects the rights of indigenous communites. Austra Berta introduced the motion to ratify the convention while COPINH spread awareness to the public. The convention was ratified in 1995 making it law in Honduras.

“After the peace convention, [COPINH] worked to rescue indigenous customs,” says Agustina.

She explains that many indigenous customs, including the Lenca language, had been lost, in part so that the people could avoid discrimination. COPINH began to fight to recuperate the customs to help give the people a claim to their indigenous rights.

From the beginning, Berta did a lot of work for indigenous women.

“It was a process,” says Agustina. “It still is a process for them to be accepted as women and not just as objects or as the husband’s wife.”

COPINH started a refuge for women who had been abused and taught women in the communities how they could report abuse when they experienced or witnessed it. They also fought for the right to education for indigenous women. Thanks to their work in the communities, they saw many young women graduate as agricultural engineers.

The list of causes Berta took on in COPINH seems to be unending. COPINH worked for the education of indigenous communities, for its religious rights and for the establishment of indigenous municipalities. It fought for the rights of the LGBTQ community. It fought against the exploitation of mines, forests, farms and rivers. It fought against the militarization of the country.

According to Agustina, Berta used communication networks to bring COPINH to an international level. She travelled to Kenai, Norway, the United States, Canada, Guatemala, Mexico, Brazil, Colombia and Australia to work with indigenous community, afro-descendants and other marginalized peoples in Honduras and in the rest of the world.

The Commitment

“Later, large dams began to come – death projects,” says Austra Berta.

Berta’s mother explains that power businesses began to construct dams on rivers in predominately indigenous regions of the country. These businesses were owned by some of the most powerful people in the country. Berta reported that 49 projects had begun construction without the prior and informed consultation with the indigenous community, as required by Convention 169.

According to Austra Berta, her daughter had been persecuted for years, but after the arrival of the dam, the threats skyrocketed. In the years before her death, Berta was the object of many accusations. She received threats of kidnapping and murder against herself and her family, even against her only grandson.

“They killed Berta minute before midnight,” remembers her mother.

Berta had left her mother’s house to live on her own just two months prior. She had bought a small house in new neighborhood on the edge of the city.

In the face of the threats against her, the Inter-American Human Rights Commission had urged the Honduran government to implement protective measures for Berta. Normally, because of these protective measures, a police patrol car passed in front of her house every night to make sure everything seemed normal. However, according to Austra Berta, the night of the murder no police came by Berta’s house.

Berta was in her bedroom when two men broke down the back door and forced their way into the house. One of the men walked into her room and fired fatal gunshots into her chest. The other went into the guest room where Gustavo Castro, a Mexican activist who was visiting Berta to help with a workshop, was staying for the week. The gunman aimed at Castro’s head but only wounded his ear. He pretended to be dead until the gunmen left, then he went into Berta’s room and found her dying on the floor. According to Berta’s brother, the family did not find out about her death until four hours after the heinous attack.

The Last Goodbye

In their final moments together in la Esperanza, just months before Berta’s death, Agustina tried to convince her sister to be more careful.

“I told her to think about Mom and her children, to leave COPINH,” admits Agustina.

She says that Berta had received a job offer in the United States as a consultant, but for Berta, leaving the fight was like abandoning a child.

The sisters shared their last hug on the corner outside of their mother’s house.

“We cried a lot,” says Agustina. “We hugged as if it was the last hug. She got out of the car and hugged me one more time.”

Even though Berta was the youngest of all of her brothers and sisters, Agustina says that she greatly admired Berta and her commitment and bravery. It was her commitment and bravery that made her stay in the country and fight in the face of danger.

“[Berta told me], ‘I have too strong of a commitment with those from Río Blanco [the community where DESA was building the dam]. I cannot leave them alone. I have a strong accusation to make,” says Agustina.

In Agustina’s mind, her sister was a revolutionary with a tremendous visions and a depth of though that Agustina never fully understood. Despite the insufferable pain of her loss, the family continues to be inspired by the impact that Berta had on the world.

“Bertita has an incredible strength. Talk about bravery; she wasn’t afraid of anything,” says Austra Berta with pride. “She was an unchanging leader.”